October 2018

The general principles of valuing enterprises apply to a cannabis company. However, the regulatory and growth attributes of the cannabis industry complicates considerably the valuation of a cannabis-related enterprise. This guide discusses unique valuation considerations for cannabis-related appraisals.

Currently, there are numerous publicly-traded companies in the cannabis area. Although there is considerable money that can be made as the market explodes, the lack of stability in terms of profitability, regulation and competition causes investments in the cannabis industry to be highly risky. For individual companies, careful consideration of the matters discussed herein is required.

Market Size and Growth

The U.S. market for cannabis products is estimated to be around $60 billion. Much of this is currently traded in the black market, so these estimates are difficult to substantiate. Worldwide, the United Nations estimates the cannabis market to be $150 billion annually.

To put the U.S. market size in perspective, the U.S. market for cannabis is around half the size as the market for beer, smaller than the market for cigarettes (but not enormously smaller), around the same size as the market for wine, and roughly twice the market size of video games. However, compared to all of these other industries, the market for cannabis is expected to grow much more rapidly, with annual growth of 20% to 30% for several years. If such growth occurs, the market for cannabis could easily double in five years.

The increase in market potential is supported by:

1. Easing consumer perceptions regarding the medical and recreational use of cannabis;

2. An explosion of the products in which cannabis and TCH (Tetrahydrocannabinol) is used; and

3. Easing regulation (see next section).

Regulation

Like most businesses and industries, a proper appraisal of a cannabis enterprise needs to consider the regulatory environment that exists. Once properly licensed, the cannabis business may face less competition than otherwise would exist, which can increase (perhaps significantly) the value of the licensed enterprise. However, the regulatory and licensing environment is changing, so the analyst needs to understand what will likely occur in the future. Absent a proper consideration of this important area, an appraisal of a cannabis company will likely be incorrect.

As of 2018, nine states and the District of Columbia have legalized recreational use of cannabis. Most states allow medical use of marijuana, although some of these place limitations on the level of THC content. Only three states prohibit cannabis for all purposes. As a result of the differences between state and federal laws, cannabis dispensaries and businesses are licensed by each state, with further regulation administered locally. Canada has legalized cannabis, and is the first major country to do so.

California (where Fulcrum is located), was the first state to establish a medical marijuana program with the passage of the Compassionate Use Act of 1996 (Proposition 215). In November 2016, California voters approved the Adult Use of Marijuana Act (Proposition 64) to legalize the recreational use of cannabis. California’s main regulatory agencies are the Bureau of Cannabis Control (BCC), Department of Food and Agriculture, Department of Public Health and Cannabis Regulatory Authority (CRA).

In contrast to the actions of the majority of states, under the federal Controlled Substances Act of 1970, drugs and certain chemicals used to make drugs are classified into five (5) distinct schedules depending upon the drug’s acceptable medical use and the drug’s abuse or dependency potential. The abuse rate is a determinate factor in the scheduling of the drug; for example, Schedule I drugs are supposed to have (i) a high potential for abuse and the potential to create severe psychological and/or physical dependence and (ii) no currently accepted medical use. Examples of Schedule I drugs are heroin, LSD, and ecstasy. Examples of Schedule II drugs (less dangerous and/or subject to abuse than Schedule 1 drugs are cocaine, methamphetamine, Vicodin, Demerol, and Oxycontin).

Currently, cannabis is classified by the U.S. government as a Schedule (Class) I drug. Multiple efforts to reschedule cannabis under the Controlled Substances Act have failed, and the United States Supreme Court has twice ruled that the federal government has a right to regulate and criminalize cannabis, whether medical or recreational. Further, the federal government criminalized marijuana under the Interstate Commerce Clause.

The discrepancy between federal and state regulation will change, most likely by having the federal government change its clearly-improper classification as a Schedule I drug. As a step towards a more accurate classification of cannabis, in June 2018, the FDA issued its first approval of a medicine derived from cannabis. Specifically, Epidiolex (manufactured by Britain’s GW Pharmaceuticals) was approved to treat two rare and severe seizure disorders (Dravet syndrome and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome). The FDA carved out an exception to the Schedule I classification of cannabis, and provided a criteria for other drugs to be similarly reclassified by the FDA.

Nevertheless, the DEA’s Schedule I classification remains at the time of this writing. Until the federal government’s position changes, the possibility of federal government action against cannabis companies (i) creates risks and uncertainties, and (ii) increases tax costs, as described in the next section.

Tax Issues

Internal Revenue Code §280(e) prevents cannabis companies from deducting normal and reasonable business expenses involving a Schedule I drug that would be deductible in other businesses. As long as cannabis is classified as a Class I or II controlled substance, only expenses classified as Cost of Goods Sold may be deducted for federal tax purposes. Cost of Goods Sold are the expenses of producing or purchasing the physical product. Costs of marketing, advertising, displaying, and selling the product, and the overall cost of running the business, are not deductible for federal income tax calculations (as would be allowed for other legal businesses). To help ensure that maximum appropriate deductions are taken, cannabis businesses, should keep records showing:

- The actual work being performed by employees, so that costs of growing, harvesting, curing, manufacturing and/or packaging cannabis are captured and classified as Cost of Goods Sold; and

- The physical space (square footage) and equipment used for the functions listed in the preceding point.

These rules disfavor dispensaries, as they are primarily involved with selling the product. However, even dispensaries may have an area in which product is received, repackaged and stored before being offered for sale.

Changes in the drug classification of cannabis will have significant positive impact on the profitability of cannabis companies because of income tax reductions The significantly increased profitability caused by putting cannabis companies on an equal footing with other legal businesses will increase the value of the company’s operations to an investor.

Other Market Changes

Although variances based on the specific strain of the plant exist, cannabis cultivation generally requires a warm temperature and long light periods. Prior to legalization, cannabis was most frequently grown in either remote areas with overgrowth (to avoid detection), or indoors. Indoor cultivation raises growing challenges that substantially increases costs when compared to outdoor growing. With legalization, considerable cost savings occurs with cultivation (i) in large farms in warmer areas (like the west coast of the United States), and (ii) in larger indoor operations with positive economies of scale. Because of more efficient farming operations and the related economies of scale, the price of wholesale cannabis has dropped steadily. Looking forward, particularly when interstate commerce restrictions ease, a squeeze between production costs and wholesale prices can make indoor growers (particularly smaller growers) vulnerable.

Cultivation competition can also arise internationally. Grow operations in Mexico and Central America have considerable cost advantages, and will cause increased competition when the international markets and related imports become legal.

Cannabis usage in forms other than smoking is an area of enormous growth. Edibles and oils (and the development of such products) creates an alternative that assists the overall explosive growth in the cannabis industry.

NAICS Classification

The North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) is the standard used by federal statistical agencies and most information reporting services to classify businesses and industries. Knowing the correct NAICS code is a starting point for obtaining certain industry information and market information regarding sales of entire companies.

The cannabis industry involves numerous businesses in the channel of distribution. As with any industry, firms can be vertically integrated. Because of the newness of this industry, inconsistencies are common, so the following list is not comprehensive or authoritative. Under the NAICS classification system, most cannabis companies will be classified as at least one of the following:

1. NAICS Code 111419 – Other Food Crops Grown Under Cover

2. NAICS Code 111998 – All Other Miscellaneous Crop Farming

3. NAICS Code 325411 – Medicinal and Botanical Manufacturing

4. NAICS Code 446110 – Pharmacies and Drug Stores

5. NAICS Code 453998 – All Other Miscellaneous Store Retailers (except Tobacco Stores)

6. NAICS Code 621999 – All Other Miscellaneous Ambulatory Health Care Services

The Income Approach

The Income Approach (specifically, the discounted future benefits approach) is the preferred valuation metric in valuing cannabis companies. This occurs largely because (i) many of these companies have not yet reached the point of stabilized profitable operations, and (ii) are growing rapidly and/or are expected to continue to do so. Reliance on the Income Approach is typically the case in any industry where:

- The industry is facing changing regulatory or other circumstances that allow the enterprise to rapidly increase its sales;

- Large capital investments are planned which are hoped to allow the subject to improve its cost structure and/or alter its productive capacity;

- Cost structures are changing as new intellectual property is discovered and deployed; and

- Cost structures and/or the means of production are changing. Examples could include (i) a prospective change in tax treatment, and (ii) moving growing from indoors to outdoors.

In term of appropriate reliance on the income approach, the cannabis industry is not entirely unique, with numerous analogies. Other industries facing somewhat similar circumstances include:

- Start-up companies in a wide range of industries – In start-up ventures, means of production, distribution, and markets are all new and somewhat untested. Start-up firms also often have complex capital structures (e.g. multiple tranches of preferred stock and/or mezzanine financing) that provide challenges when dividing value among different ownership classes.

- High-technology firms whose products have large potential, but which have not yet obtained widespread acceptance;

- Biotechnology firms, who face a daunting regulatory environment or changing means of production;

- High growth companies in a wide range of industries, with rapidly growing sales and changing cost structures; and

- Any enterprise with intellectual property that discourages the analyst from making comparisons between the subject and other potentially-comparable sales of companies or publicly-traded stock.

When applying the Income Approach, the discount rate and capitalization rate are higher than what would be expected in other circumstances. Purely formulaic approaches to the buildup or other calculation of a discount rate will provide too low of a discount rate, and hence too high of a value. Stated otherwise, a proper discount or capitalization rate will include a company or industry rate premium. The proper amount of such a premium requires appraisal judgment and experience.

Major Industry Participants, and the Market Approach

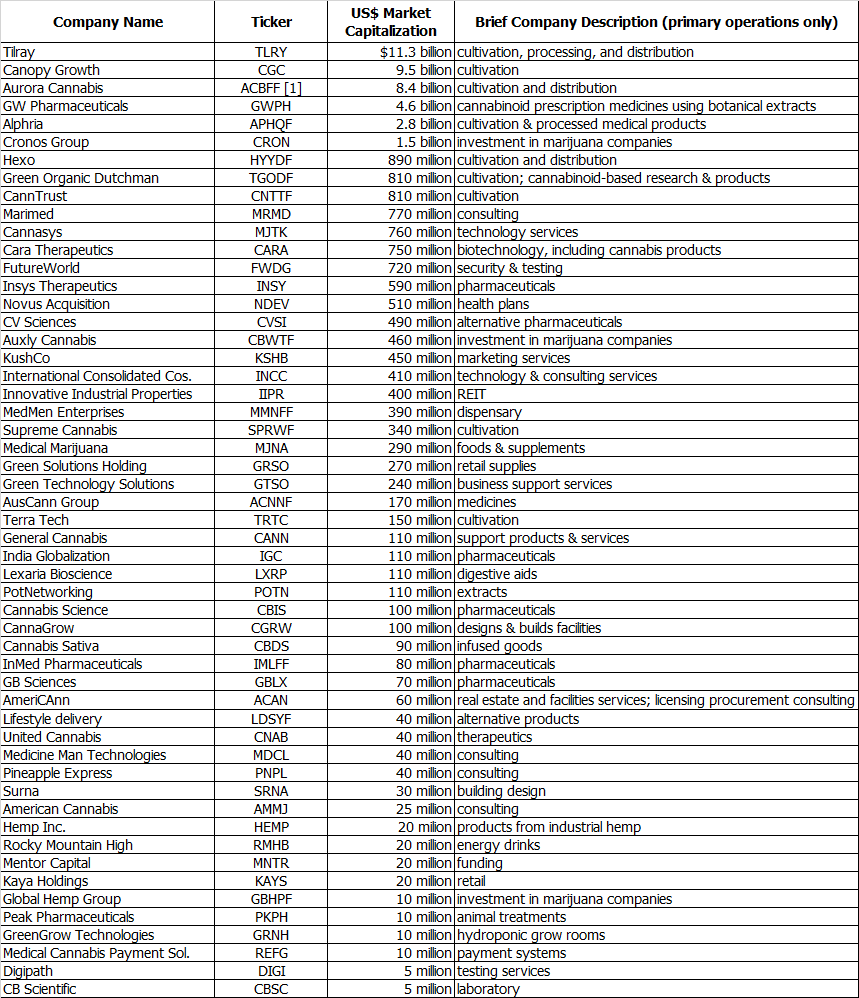

There are numerous public companies in the cannabis area. In large part because of legal and regulatory issues involving the U.S. federal government, a disproportionate number of these companies are listed on Canadian stock exchanges. A partial list of the publicly-traded cannabis companies are identified in the exhibit at the end of this guide.

The stocks of publicly traded companies, and the raising of funds for privately-held companies reflects the belief that there is in process a global paradigm shift transforming the cannabis industry from a state of prohibition to a state of legalization. However, as described above, the legalization process is still in its early stages. As the number of countries with legalized uses increase and such new regulation “quirks” are worked out, numerous and sizable additional opportunities for market participants will be created.

In many industries, use of publicly-traded companies are not a preferred application of the Market Approach. This occurs because there are often too few publicly-traded companies that have comparable operations, risk, management and size. In the cannabis industry, caution still must be exercised. However, the large number of smaller cannabis companies allow the analyst to give consideration to a Market Approach using publicly-traded companies.

As should occur in practically any appraisal of a smaller private company, the appraiser should consider sales of entire companies as an application of the Market Approach. However:

- There are fewer reported sales of cannabis companies than one might expect. This occurs because:

- Regulatory concerns diminish the desire to report relevant sales; and

- Because the industry is young, the motivations for sale of companies with good prospects are not as great as what occurs in more mature industries.

- It is difficult to obtain data regarding the financial statements of the companies (or pieces of companies) sold.

- For the company sales that are reported, the sales multiples generally vary from the same multiples derived from publicly-traded companies. Generally, the available data regarding sales of entire companies in the cannabis industry indicate a valuation pricing that is not near as expensive as is indicated by the public companies. Considerable thought and attention is needed if one attempts to reconcile the apparent price discrepancies.

Partial List of Publicly-traded Cannabis Companies

As of this writing, the following table identifies a sample of the publicly-traded cannabis companies. The trading prices of these companies are quite volatile, so the data needs to be updated for any actual analysis or other use. The purpose of providing this list is only to (i) show that even an incomplete list of cannabis companies is long, and (ii) the size range is broad, which provides the opportunity to consider the use of a publicly-traded Market Approach for smaller appraisal subjects.

(1)Scheduled to trade on the NYSE as ACB

There are well over 50 public companies that are smaller (in terms of their market capitalization) than the companies identified in the preceding table. The market has substantial interest in supporting such companies, with new public offerings occurring.

Although there is often a challenge when comparing a publicly-traded company to a private enterprise, the large number of public companies should not be ignored when valuing a private cannabis firm, particularly if the private subject company is larger.